The Unit When You Read Those News Stories

Oct. vii, 2019, x a.m.

"With the advertising people looking at the ad metrics, the subscription people looking at subscription metrics, and journalists looking at outdated metrics…nobody was looking at these metrics together to get a clear view of the business equally a whole."

Imagine you're a barista at a coffee shop. You may have no groundwork in business, finance, or information analysis — just you all the same probably have a decent handle on how the company yous work for makes money and what part yous play in that process.

You know that each cup of coffee you lot sell costs the customer $2 or $3. The company makes that amount minus the cost of the coffee grounds and the loving cup, with some fixed overhead costs. If y'all sell more cups of coffee, or get customers to purchase more than expensive drinks, the company makes more money — and with fifty-fifty bones arithmetics skills, you lot can probably estimate in your head about how much more. If you waste supplies or work a boring shift, the company makes less coin. Simple.

I've idea about this in recent years because I've spent a lot of time sitting in coffee shops crunching data about business organisation models for digital news. A collection of benchmarks and all-time practices from that work was published in the digital pay-meter playbook, released terminal month in a partnership between The Lenfest Institute and Harvard's Shorenstein Eye.

Through the course of that reporting, it struck me that baristas — and well-nigh employees in other industries — have a improve understanding of their roles in their arrangement's overall business than journalists do.

Near journalists know but a few things about the companies they piece of work for: They know the news industry, peculiarly the local news business concern, is struggling. They may generally know that if their articles attract more pageviews, the visitor makes more money from ad— though they probable have fiddling sense of how much. And in the last year or two, they've probably heard an proclamation or two from an eager executive well-nigh the visitor's new, or newly emphasized, digital subscription or membership initiative.

What they don't know are the answers to some important questions, like: How much revenue does a typical article I write generate from advert? What if information technology goes viral? Is it improve for my commodity to get lots of pageviews or for it to concenter digital subscribers? How practice those two goals chronicle? Subsequently all, the coverage that generates the most clicks may by completely different from the stories that attract subscribers.

Indeed, when trying to get basic metrics from publishers virtually the value of a subscriber, the marginal impact of a pageview on advertisement revenue, and other primal metrics, I constitute that many publishers either didn't have clear answers or that the information was siloed — with the advertising people looking at the advert metrics, the subscription people looking at subscription metrics, and journalists looking at outdated metrics such equally how ofttimes their articles made the front page of the newspaper. Nobody was looking at these metrics together to get a clear view of the business equally a whole.

It's time for the news manufacture to have a clear grasp on the unit economics of journalism content. And while we don't yet have all of the answers, some of the research and metrics nosotros've gathered to appointment can point us in the right direction.

Unit economic science for news: Some central metrics

There are a number of different metrics that can help journalists and news organizations understand their businesses amend — but to get-go, publishers can go a long way by starting with just 2 central data points.

Client lifetime value (CLV)

The metric publishers should know is customer lifetime value, a mutual metric in subscription businesses that looks at the average revenue generated by one new subscriber over the lifetime of the subscription.

There are many ways to summate CLV, just in the simplest terms, it can be calculated past multiplying the average monthly revenue per subscriber by the expected lifetime of the digital subscription, meaning how long the average user will remain subscribed before they cancel. For a subscription business concern that averages $10/month per user and retains its subscribers for 20 months on average, the CLV would be $200. Every new subscription sold will generate, on average, $200 in new revenue.

The average revenue per subscriber can be calculated by dividing full monthly subscription revenue past total subscribers over a six- or 12-month flow. The average lifetime of a subscription can be calculated in a number of ways — some publishers have sophisticated retention curve models — but ane elementary and easy calculation that works for about purposes is:

one ÷ monthly churn charge per unit

This tells y'all the average number of months a subscription volition final. Publishers who run paid advertising campaigns to acquire new subscribers may also choose to subtract the boilerplate cost per new acquisition — which is

full paid marketing spend per month ÷ total new subscribers generated per month

— from their CLV.

Our benchmarks prove that a publisher performing in the 80th percentile — the typical range for a daily newspaper putting at to the lowest degree some effort into digital subscription sales — has a CLV of $217 for a digital subscriber. For publishers putting more than focus on digital subscriptions the numbers can be substantially higher — oftentimes in the $300–$350 range.

About publishers accept some calculation of CLV used by their finance or consumer marketing departments — and if they don't, they should. But beyond a relatively small team managing digital subscriptions, well-nigh people at a typical media visitor don't know this number.

Digital advertizement revenue per one,000 impressions (RPM)

The 2nd metric publishers can await at to understand the unit economics of their digital business is digital ad acquirement per ane,000 impressions, too called RPM. In its simplest form, RPM is calculated by dividing digital ad revenue by total pageviews and multiplying that number times one,000. Put simply, information technology tells a publisher how much ad revenue they generate for every i,000 pageviews they serve.

However, while every publisher should know their overall RPM number, it can also be a bit misleading because non every pageview generates the same amount of advertisement acquirement. Well-nigh publishers do not sell out all of their bachelor inventory with loftier-charge per unit, directly sold advertisements. Instead, at the margins, their pageviews are primarily monetized by programmatic ads that can yield relatively little revenue per pageview. If a publisher increases their pageviews marginally to a higher place their usual baseline, their increase in ad acquirement primarily comes from this category of lower-yield advertisement.

For day-to-mean solar day editorial decisions, then, what may matter more is marginal RPM: the advertising revenue generated from the next 1,000 pageviews a publisher might generate. For most publishers, this means RPM for programmatic advertizement just.

It's likewise all-time to look at this metric, if possible, for content pages only. Ads sold on the home page or department front pages are nonetheless relevant to the business organisation, just are not relevant to the impact one article or another might have on the concern.

Though we weren't able to gather a full benchmark for this metric from hundreds of publications, my informal survey of publishers suggests that most publishers are monetizing their pageviews in the range of $xx–$25 per thousand pageviews overall and in the range of $6–$10 at the margins, primarily from programmatic ad. As with CLV, in many organizations, noesis of this metric is largely siloed inside the digital advert section.

Case study: 1 digital subscriber or 48,000 pageviews?

By knowing just these two basic metrics, publishers (and journalists) can learn quite a bit about the unit of measurement economics of their business concern and the value of their day-to-day work.

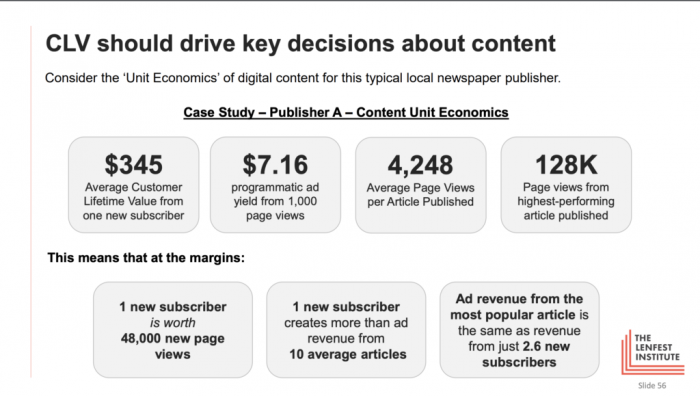

Every bit a example report, consider this metro daily newspaper — we'll call it Newspaper A — that was kind enough to share these two metrics and some basic traffic information with me.

Newspaper A has a client lifetime value of $345, a flake higher than the norm. Based on its calculations, the average new digital subscription sold volition be worth nearly that much over the course of the subscription. (If this seems loftier, it's because the publisher in question has a higher-than-average subscription price and very good retention metrics.)

Newspaper A too generates $21.44 in total ad per 1,000 pageviews, or $7.16 per 1,000 pageviews from programmatic advertising but. Its sell-through rates for non-programmatic ads are well below 100 percent of impressions, meaning that the programmatic number is a proficient proxy for total revenue from the next ane,000 pageviews they generate.

From merely these few facts, we can learn a lot most the unit economic science of Newspaper A'southward journalism.

For example, we can tell that an article that attracts one new digital subscriber will, on average, generate as much acquirement for the company as an article that generates 16,000 pageviews monetized through direct-sold advert, or an commodity that generates 48,000 new pageviews monetized through programmatic advertisement.

We reached that figure by taking the $345 CLV dividing it by the $21.44 and $seven.sixteen figures in digital ad revenue per 1,000 pageviews and and then multiplying each 1,000.

$345 ÷ $21.44 × 1,000 = 16,090

$345 ÷ $7.16, × 1,000 = 48,184

As a journalist or editor, knowing this fact alone could shift your perspective about what kind of coverage to focus on.

Looking at data for all articles published past Newspaper A in a particular week, the average article generated about 4,250 pageviews in the month later it was published. Using the CLV and marginal advertizing revenue metrics, we can therefore say that the average article generates $thirty.43 in programmatic ad revenue for the visitor.

Put another way, an commodity that attracts ane new subscriber generates the same revenue as about ten average-performing articles.

In contrast, the acme-performing commodity from that fourth dimension period attracted about 128,000 pageviews, or $916.48, equivalent to the revenue generated by virtually 2.6 subscribers.

Paper A cautioned that its CLV metric may be a bit inflated because its subscription organization does not arrive easy to gather reliable information. If we assume the more typical CLV benchmark of $217, the numbers tell a similar — if less farthermost — story:

- One new subscriber would be worth the same as ad revenue from xxx,000 pageviews monetized through programmatic ads.

- Ad revenue from one new subscriber would be worth the same equally programmatic ad acquirement from seven average-performing articles.

- The top-performing article would be worth almost iv.2 subscribers worth of programmatic advertisement revenue.

Revenue metrics and the newsroom

What would happen if news organizations shared and socialized this kind of information across their unabridged company — and, in particular, inside the newsroom?

While no organization I know of has fully shared this information, my prediction is that it would help journalists exercise their jobs better. In today'south metrics-driven surround, the metrics actually available to journalists are primarily measures of full reach: ranked lists of articles by pageviews and in some cases more detailed data related to time spent on a page or other engagement metrics.

Fifty-fifty if they aren't doing it intentionally, it would be natural for reporters and editors to respond to their successes and failures on these metrics and to adjust how they produce stories. Articles with sensational clickbait headlines get more pageviews; people producing headlines see that, and respond in kind. Stories that mention particular celebrities or politicians attract more clicks, so of course journalists are tempted to shoehorn those characters into otherwise unrelated stories. Stories covering a national or international issue generate a lot of broad interest in national media, and so of course local journalists are tempted to rehash those same stories — even when there'due south nada new to add.

Only we know that the coverage that attracts and retains subscribers is frequently different from the reporting that generates the virtually pageviews. Sometimes a niche topic — such as coverage of a loftier school sports team or highly local result like weather — volition be the sole reason for subscribing for a subset of users. More generally, users who subscribe tend to prefer reporting that is distinctive, local, and relevant to their daily lives over stories that are sensational or a rewrite of news they've seen elsewhere.

If newsrooms could view successful coverage not just every bit content that generates clicks, but also as journalism that delivers value to subscribers, it stands to reason that they would respond to those cues in the decisions they make mean solar day-to-day. (Indeed, clarifying and measuring success across the entire company is the only way I've seen businesses transform in the way that many news organizations must in gild to survive.)

So how can publishers do this? While no publisher I know would say they've fully figured it out, many have experimented with versions of this arroyo. Hither are four simple starting points based on what nosotros've seen work beyond the industry:

- Socialize key "unit economics" metrics. First with the basics: For most publishers, there's no reason that everyone in the company shouldn't empathise and know key metrics such as CLV and marginal advertising revenue.

- Basic daily reporting. This is similarly straightforward, just many publishers don't do it: Everyone in the newsroom should know daily — or at worst, weekly — how many digital subscriptions were sold and from which sections of the site. I publisher who shared its written report with me sends out a daily email to the newsroom that recaps the site's traffic from the previous twenty-four hours. The study shows the number of new subscriptions per section, lists every URL that led to a new subscription, and highlights the authors of those articles.

- Subscriber content-consumption reporting. If a publisher has the ability to segment subscriber traffic from non-subscriber traffic, they should provide this data to the newsroom equally well. Knowing that subscribers are engaging more deeply with commodity 10 while non-subscribers are clicking on commodity Y tin tell us a lot. I know from publishers who have tried this, for example, that the content viewed past subscribers correlates at least loosely with the coverage that generates new subscriptions. Ane publisher implemented a simple version of this using Parsely: On their typical article traffic report, they added a section that shows what the elevation story read past subscribers was the twenty-four hours before.

- Subscription influence reporting. Some publishers have experimented with a "subscription influence" ranking chart meant to mimic the look and experience of the typical "most viewed" rankings that journalists see. This ranks a particular week's manufactures by what pct of new subscribers viewed that article on their path to subscribing or immediately after subscribing. Ane publisher with this kind of dashboard segmented the data to testify, for each commodity, show how many subscriptions the article influenced at all (significant the user viewed the commodity in the 30 days before subscribing), how many subscriptions it "highly influenced" (meaning the user viewed the commodity within 7 days of subscribing) and how many it "directly influenced" (meaning the user viewed the article in the same session as or directly subsequently subscribing). This is better than but looking at the terminal article a user viewed earlier subscribing, which seems not to exist a very good predictor of anything in and of itself.

These iv steps just scratch the surface of what is possible with this shift in thinking. Hopefully, equally information becomes more easily available and publishers become increasingly focused on digital revenue, these kinds of developments will make their way into many news organizations.

Looking beyond content

Across agreement the relative value of unlike content produced by the newsroom, having a firm grasp on these kinds of metrics tin can also have broader implications for how publishers look at their business models.

For case, publishers can use these metrics day-to-mean solar day as they make decisions most meter limits and other access rules. If a publication lowers its meter limit from 5 gratis manufactures per month to three, it should enquire non only how many pageviews information technology might lose, just also what those pageviews are worth — and how many new subscriptions the change would need to generate to constitute a net positive.

More broadly, understanding these metrics tin help publishers understand how they should be allocating their resources. In a recent survey for the Reuters Institute's Journalism, Media and Technology Trends and Predictions 2019 report, three quarters of news publishers surveyed said they devoted less than 25 percent of their company'due south resources to growing their subscription products, and almost 4 in 10 said the percentage of their resources devoted to subscriptions was in the single digits. If publishers were more focused on metrics similar CLV, they might be inclined to shift that balance then that — at the very least — subscriptions and advertizement were treated as equal goals.

Matt Skibinski is a reader revenue advisor for the Lenfest Institute.

Source: https://www.niemanlab.org/2019/10/one-subscriber-or-48000-pageviews-why-every-journalist-should-know-the-unit-economics-of-their-content/

0 Response to "The Unit When You Read Those News Stories"

Post a Comment